It’s just past the halfway of 2011 and I thought I share some albums I’ve enjoyed.

My 2011 so far.

•August 24, 2011 • Leave a Comment“Father, Son, Holy Ghost” – Girls

•August 24, 2011 • Leave a CommentOkay, so the new Girls album has dropped. Their self professed “3rd Record”, “Father, Son, Holy Ghost” comes after the debut album called “Album” and the 2009 EP “Broken Dreams Club”. The first song to be released off the album was “Vomit” and it really found Girls experimenting with the almost-twee pop that they had become known for. To be totally honest, I wasn’t super excited about hearing this cd. I saw them early in the year, and thought they were pretty disappointing. But I’m glad I did listen to it, because it really is a solid album.

.

.

The first thing I noticed about “F,S,HG” was the mixing, unlike “Album”, the drums can be clearly heard and are not hidden away in the background of the track. This makes the album have a more rock-like feel and allow the band to have some heavy jams like on the track “Die”. This was done seemingly because of the more vintage rock style that this album is going for and while it still retains the cutesy love songs from the band’s debut, they’re fleshed out sonically and have a bit more grunt on them. One thing I don’t like about the mixing of the album though, is the fact that the bass is sometimes masked by the bass drum. The band’s debut was great because of the interplay between the guitar and bass and I do feel that the band slightly looses this on some tracks.

This review would kind of be a diservice if I didn’t mention the track “Die”. For fans of Black Mountain, you will love this track, it’s heavy and has some killer riffs, along with some great guitar playing. It’s an almost completely different style to the rest of the album, but somehow it doesn’t feel too out of place. Although I do think the long ending and slow down is a bit laboured and is quite obviously an attempt to get the album back on track towards the more twee stylings of the rest of the album, and while I like that they’ve tried this is does seem a little artificial.

The first track that was released from the album was “Vomit”, and it’s a more sprawling track than the rest and I’m really liking the groove of it. The guitar’s a bit more ambitious and is brilliantly played, it’s a style that I would’ve loved to see the band experimenting more with, especially considering their somewhat famously disappointing live shows.

Reading this you may think I’m really not liking the album, but I just think the bands missed out on an opportunity to make something great. I love a lot of the songs and while the mixing is at times harmful to the music, it does allow the band to experiment in a heavier sound. But while they’ve successfully made some great “crossover” songs between the two styles, it seems a little too eclectic. I would’ve loved to hear Girls’ write a few more heavier songs and make an album from them (it would have been great), but unfortunately they’ve tried to take the best of both worlds and have gotten stuck halfway between two extremely good albums.

In the end, stick to the songs, they’re great and it really shows the qualities of these songwriters. But for some reason, the album kind of loses it’s charm and edge. The band needs to be applauded for trying something new though and I’ve got a lot of time for them.

Rating: 7/10

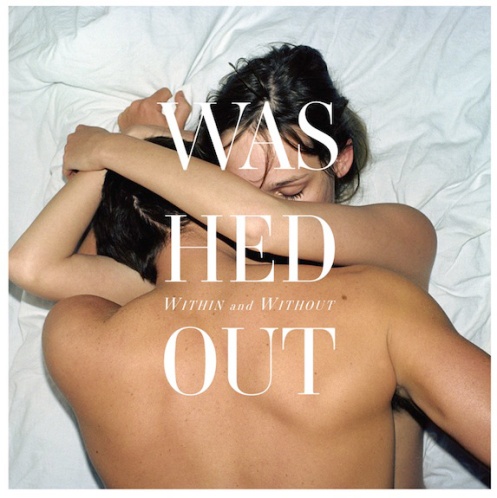

“Within And Without” – ‘Washed Out’

•August 14, 2011 • Leave a CommentWashed Out is Ernest Greene, bedroom synth-pop soloist hailing from Georgia, USA, recreating whatever disco left behind into the consistency of a stretched-out piece of chewing gum. Pace is utterly devoid across its nine tracks. It is hard to believe – let alone conceive – an individual as sophisticated as his music, was capable of such an exclusive endeavour. Released – I believe – sometime last month Within And Without is Greene’s debut, and what a blast it is:

“Within And Without” – ‘Washed Out’

“Within And Without” – ‘Washed Out’

Within And Without is heavy on the reverb. Dreamy, ‘gazey atmospheres projected from some faraway obscurity. Melancholic downtempos sweep up lyrics in a bleak, slow-mo whirlwind, while any percussive emphasis seems dulled in a thick, impenetrable treble overcoat. This gives the feel of an overall monotone haze. Predominantly synth, Within And Without is as its name implies: very Washed Out. The album feels hung-over. Or, as one might traverse a dream: not-all-there. It is not unenjoyable; contraire. It is quite. It is relaxing, to the degree of chillwave – so, think The Phenomenal Handclap Band minus its psychedelica, or even Chicane. If you’ve never heard of either of them, or disliked them altogether, Within And Without probably isn’t for you. Despite its chillwave vibes, elements of dance – the synth-beats, the glassy ambience – are an ever-present characteristic, though not so much as to a boppy consistency as to a trudge or gentle sway.

At just over forty-minutes, Within And Without is the toddler that drags their feet across the ground making an otherwise straightforward journey, mind-numbingly tedious, to great effect. Its deception lengthens it to the feeling of an hour, while its tracks are doubled from the averaged four-minutes to eight. Time slips away, then, while Within And Without swallows you into its world of semi-transparency and fatigue. One gravitates to it as one gravitates to sleep, or chocolate, or sunlight. Too much of a good thing, and you start to feel sluggish, sick almost. If only for this bittersweet phenomena, check it out.

Such as it is, chillwave has a tendency to bleed from one track to the next, often seamlessly without one noticing. It is largely responsible for undefinable disinterest – that is – why am I not liking this? Within And Without barely establishes a crescendo at all, but it’s careless to simply lump it into the aforementioned. Rather, Greene has carefully constructed miniature breaths between each track, fade-outs and ins that qualify movement, change. This gives the listener a brief moment to compose themselves with anticipation. What may be bogging you down instead is characteristically beat-oriented style. They drive each and every track; yes, there is some danger to be found here – repetition. But it’s not enough to impact Within And Without’s individuality. What I remember most about it is its opening, “Eyes Be Closed”: its frizzled synth contained in an hourglass of phantasmal reverb. “Soft” and its spot-on conveyance of physical sensation through aural stimulation. But perhaps the most effective track – and my personal favourite – is “You and I”: pace set at a trudge, laboured beats and long-winded articulations somehow cowering behind distortion. Trimmed in the softest velvet.

Reviewer’s Pick: “You And I”

Stand-out Tracks: “Eyes Be Closed”, “Soft”, “You And I”, “Within And Without”, “A Dedication”

Rating: 4/5

Until when,

The Enantiomorphic God

“The Words That Maketh Murder” – PJ Harvey

•August 13, 2011 • 1 Comment

The Words That Maketh Murder was released on the 6th of February, 2011 and written by PJ Harvey. It appears on her eighth studio album, “Let England Shake”, which was released on Island Records worldwide, and Vagrant in the United States1. It features PJ Harvey on vocals, saxophone and auto-harp, long-time collaborator John Parish on guitar, trombone and Mick Harvey on bass, harmonica and drums2. It was produced by Flood, who has produced 4 other PJ Harvey albums. “Let England Shake” was recorded in a Church located in Dorset, UK3.

————————————————————————–

INTRO (0:00-0:14)

The song starts with a sole auto-harp playing a string of descending chords, that make way for the main chord progression and the beginning of the percussion. The percussion has a heavily reggae influenced beat (which is a common occurrence in the album), and the auto harp follows the beat.

VERSE (0:14-1:06)

PJ Harvey’s vocals cut in and are delivered in a subtle but wailing manner, coupled with the main minor chord, it transforms a reggae influenced song in to a haunting song about war and death (“I’ve seen and done things I want to forget; I’ve seen soldiers fall like lumps of meat”). Obviously channeling a man at war (“Longing for a woman’s face”), PJ Harvey talks about the atrocities of war, trying to create a visual picture of war. The lyrics are delivered one line at a time and sung on the steady chord, while there is a break in the lyrics for each descending chord progression. Finishing the first verse with the line (“The words that maketh murder”), it signal a start to the chorus.

CHORUS (1:06-1:34)

Right as the chorus starts, we hear the trombone (played by John Parish)and the saxophone (played by PJ Harvey), which holds a fairly straight beat, when compared to the drums. PJ sings the first repeated line (“These, these, these are the words”) on her own, while a backing vocalist can be heard singing on the next line (“The words that maketh murder”) along with PJ. The first line is delivered in a progressively more distraught manner each time it is sung, which gives the chorus a crescendo towards the end, while the instrumentation remains steady.

BRIDGE (1:34-1:46)

The main vocals stop and we hear the backing vocalists come to the forefront, singing the chorus lines.

VERSE (1:46-2:19)

The auto-harp fades out as PJ’s vocals cut back in, mirroring the first line of the first verse (“I’ve seen and done things I want to forget”). The bass can now be heard, which along with the bass drum almost sounding like a beating heart. The vocals are delivered in a softer way, but as the auto-harp slowly fades in the vocals go back to the wailing style that is heard throughout the rest of the song.

CHORUS (2:19-2:43)

The chorus’ instrumentation remains the same, but with changed lyrics (“Death lingering, stunk, Flies swarming everyone, Over the whole summit peak, Flesh quivering in the heat.

This was something else again. I fear it cannot be explained.”), that sound even more haunting than the previous ones.

OUTRO (2:43-3:41)

There is a key change and we start to hear backing vocalists sing the line, “What if I take my problem to the United Nations?”, which is borrowed from the Eddie Cochran song Summertime Blues4. PJ then joins, with a wailing and distraught voice. The drum beat stays the same, but the most notable difference is the addition of a slide guitar that has an echo and sounds like a cross between a cry and a wail, it’s not loud and almost sounds like it’s trying to be louder than it is, like it is trying to “be heard”. The song abruptly stops and all that can be heard is the remaining instruments’ echoes.

————————————————————————–

The vocals are something that really need to be examined, PJ Harvey’s previous work has a very different vocal delivery. The wailing nature of them is completely different to anything she has done before and it’s the first thing that hits you about the song, if you’ve heard any previous PJ Harvey albums. She explained, “…the nature of the words are often addressing very dark weighty subjects. I couldn’t sing those in a rich strong mature voice without it sounding completely wrong. So I had to slowly find the voice, and this voice started to develop, almost taking on the role of a narrator. I could visualise the action taking place on the stage, and the narrator’s on the side relaying the information of the action. I had to find the right voice to carry out the action as if I were the voyeur, and had to relay the story.”. Her voice carries an amount of emotion that few singers can, and at times (the second verse) it is scaled back to accentuate the emotion in the crescendos and the more prominent lines (“The words that make, the words that make, Murder.”).

The first instrumentation that you hear is the auto-harp. It’s a rare instrument to hear at the forefront of a modern day song, and gives the song a unique and old feel. The auto-harp echoes throughout the song and gives it a very holy sound, which is very fitting as the song was recorded in a church. The backing beat is influenced by reggae and stays steady for the entire song, to make up for the steady beat the crescendo’s and changes in the song are achieved by changes of the emotion in the vocals and a key change in the outro. The drums also sound like an warped version of a march and I think it’s vital to the song that the drums are steady (like a marching song) throughout as it gives it a war/army feeling to it. In the chorus a trombone is heard and further makes the song sound like a heavily warped marching band song. The auto-harp (largely playing a minor chord) and almost weeping vocals allows the song to sound sorrowful, this, coupled with the unexpected steady march-like drums allows for a juxtaposition of both order and the effects of war.

The strength of the song is in the lyrics and the instrumentation enhances them, making them more powerful. Such an example is the slide guitar in the outro section, it sounds restrained and imprisoned, almost as if wants to be heard, it wails and weeps, but never really comes to the forefront of the song, seemingly answering the repeated lyric “What if I take my problem to the United Nations?”. Lyrics like “I’ve seen soldiers fall like lumps of meat” are immensely powerful and are hard to miss when listening to the song, the fact that they really hit the listener allows for the lyrics/vocals to stay in the forefront of the entire song, because the listener is always being forced to listen to the lyrics. The recounting of the atrocities of war, “Blown and shot out beyond belief. Arms and legs were in the trees.”, is unspecific in terms of an exact war. What this tells me is that the song is about war in general, not being editorial or critical, just explaining the harsh nature of war. In an interview, she explained that she “…was looking at artwork like Goya’s “Disasters of War” series and Salvador Dali’s pictures from the Spanish Civil War era.”. Why an album about wars came about at this time, is probably largely due to the wars in bother Iraq and Afghanistan, speaking in an interview, PJ Harvey said that she was influenced a lot by war photography Seamus Murphy (who spent almost a decade in Afghanistan), she added, “I was extremely moved by an exhibition I saw of his called ‘A Darkness Visible’. So much that I actually I got in touch with him because I wanted to speak to him more about his experiences being there in Afghanistan.”.

Instead of using the lyrics to make an ugly album, which could have worked with the harsh lyrics and her ability to make amazing, yet harsh and abrasive music (see “Pig Will Not” on PJ Harvey’s collaboration album with John Parish, “A Woman A Man Walked By”), she used instruments such as the auto-harp which sounds quite beautiful. She explains, “It’s to do with the world we live in. That world is a brutal one and full of war. It’s also full of many wonderful things and love and hope. And I tried to offset the brutal language with very beautiful music.”.

In terms of politically charged music, modern times have been relatively plentiful. Artists like Anti-Flag and Rage Against The Machine have a whole back catalogue full of political music, in fact when a leading US radio programmer allegedly (they later denied the allegations5) released a list of songs that they felt were unsuitable to play after the vents of 9/11, they listed all songs by Rage Against The Machine6. Even though the list was denied to be real, it shows how much of an impression a song can have on someone and the fact that people believed that a list was a possible scenario, tells me that it wasn’t that outlandish to suggest such a thing. Other acts like Neil Young, Green Day have written whole albums criticising the US government, with “Living With War” and “American Idiot” respectively. While artists like The Decemberists and Arcade Fire have written songs like “16 Military Wives” and “Intervention”, both protest songs about the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The reason I love this song as a political piece of music, is because while a lot of politically charged songs sound preachy, “The Words That Maketh Murder” does not come off in that way. It’s a song about war, not a song necessarily critiquing war, which allows the song’s message to be entirely up to the listener. The song slowly broods and flows describing war, while not vocalising any opinions (in fact, the lyrics are channeling a man at war), not until the end does it become a song that seemingly become critical, with the lyric, “What if I take my problem to the United Nations?”. It never voices opinion, I find sometimes gets in the way of the message of the song, by never voicing an opinion, it forces the listener to actually think about the subject, which in this case is a delicate subject.

What sets apart an album like “Let England Shake” and in particular the song ‘The Words That Maketh Murder”, is the fact that it is an album/song about war not an album/song protesting war. It doesn’t tell people to “impeach the president” (see “Impeach The President” by Neil Young), which sounds preachy, it describes what war is like. But more importantly it is made by someone living in the UK (a country that has a major presence in both wars), while it is not uncommon to hear a politically charged album from an American in recent years, it is rare to hear one from a UK artist and more specifically an English artist. In fact The Guardian writer Matthew Herbert wrote about “a defining silence in political music” and contended that “In an age of such infinite and brilliant possibilities of technique, combined with the urgent politics of now, why have music and musicians lost the urge to challenge, investigate, invent and unite?”, and while I disagree with this in the case of American music, it has most definitely hit the nail on the head, with respect to modern UK music.

Statements are all about timing, the UK is involved in two wars and yet there are essentially no songs about the subject made by UK artists. PJ Harvey has released “The Words That Maketh Murder” about war when it seems that no-one else is willing to do so. The choice to make the song about no specific war has the ability to stay relevant and not age badly, something that a lot of political/protest songs have succumb to. Coupled with the harsh lyrics and beautiful yet sorrowful music, I really do believe that “The Words That Maketh Murder” is one of the best songs ever written about war.

“Born In The USA” – Bruce Springsteen:

•August 11, 2011 • 1 CommentA symbol of nationalistic pride, Bruce Springsteen’s Born in the USA subsists patriotically in one form or another, despite its antithetic sentiments. The last, burnt-out refuge of Republican scoundrels still clinging to outdated, Capitalistic xenophobias, yellow-man effigies ‘twixt warmongering romanticisms and unrealities. Nearly twenty-seven years later and already twenty-six years too late, conservative talk-show host Glenn Beck:

… [W]as shocked, shocked to discover that for all these years he’d been rocking out to a song about a bitter down-and-out Vietnam vet who has been kicked to the curb by the aforementioned USA.

(Beyerstein; p1)

***

The 80s decade saw a shift from conventionality – again. From disco to synth-pop – not altogether different from folk/blues transition from rock ‘n’ roll in the 50s. 60s liberalisms resurfaced, rife with androgyny: Boy George, Garry Glitter, Johnny Rotten, Sid Vicious, not to mention carry-over megastars from the previous decade, like David Bowie, Michael Jackson and Freddie Mercury’s Queen. Punk saw its first schisms into a heavier, hardcore post-punk with artists such as The Cure, New Order and U2 prospering. Five years post-Vietnam; Republican Ronald Reagan had just succeeded Jimmy Carter for the American Presidency; the end of the decade would see the first to years of the G.H.W. Bush Administration. Suffice to say, dissent was endemically popularised worldwide.

Springsteen’s seventh studio album (Columbia Records) of the same name produced seven Top Ten singles – one of only three other albums to do so – while the subsequent Born in the USA Tour lasted two successful years. Politicians leapt before thinking, seized a chance to harp on Born in the USA, and plugged it with jingoistic bastardisations of its anthemic chorus; as Hitler did unto Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries. With the song’s release on June 4th 1984, Springsteen unwittingly became the country’s subliminal pinup-boy. Move over Uncle Sam, here was a man without:

… a smidgen of androgyny… who, rocketing around the stage in a T-shirt and headband, [resembled] Robert DeNiro in the combat scenes of “The Deerhunter”. This is rock for the United Steelworkers…

(Will; p1)

Annie Leibovitz’s renowned photo of Springsteen’s blue-jeaned, red-capped, white-shirted rear plastered across the American flag galvanised propagandist patriots: finally, a buff, heterosexual working-class-ass, an embodiment of the so-called American Dream, tangible. Reagan even managed to slip Springsteen somewhere into his 1984 re-election campaign, stating that:

America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside our hearts. It rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire: New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen. And helping you make those dreams come true is what this job of mine is all about.

(Reagan; 1984)

Danny Federici’s piano/synth soared across Max Weinberg’s pounding snare-drum, and the predictable yet seductive repetition of notes from start to finish, stole any lyrics hiding behind a raspy-voiced Springsteen between sing-along choruses. What anybody cared about, it seemed, was in those choruses – overriding Born in the USA’s anti-war communique about post-war suffering and its vilified veterans. A mixed-message reaction ensued; Springsteen responded at the time by telling Rolling Stone Magazine that:

I think people have a need to feel good about the country they live in. But what’s happening, I think, is that that need is getting manipulated and exploited. You see that in the Reagan election ads on TV.

(Springsteen; 1984)

***

Born in the USA follows an unnamed, down-and-out protagonist’s journey from deadbeat, to criminal, “Born down in a dead man’s town… I got in a little hometown jam…” from soldier back to criminal again, “Down in the shadow of the penitentiary… I’m ten years down the road… I’m a long gone Daddy in the USA…” Recurring on the second- and fourth-beats of each bar, Weinberg’s emphatic snare-drum encapsulates unwavering, small-town drudgery as well as wartime monotony, rolling occasionally during the choruses and towards the end of lines, into a flare. It gives the song pace, and is effectively its beating heart – the heart of the protagonist, the non-stop rhythm of cannon/bullet fire, and its demise come song-end. For example: “I had a brother at Khe Sanh / Fighting off all the Vietcong / (*roll) / They’re still there, he’s all gone… / (*roll*).” These flares accentuate moments of intense, emotional passion between steady beats in an attempt to redirect our attention to the lyrics – like italicising a sentence, indicating its importance. Khe Sanh’s significance is merely a metaphor demonstrating the pointlessness of warfare – from the 21st of January through to April 8th, America defended and later abandoned after their subsequen victory, their base at Khe Sanh. By its end, there were 7,482+ casualties, 1,542 fatalities, 5,675 wounded and 7 missing. This amazing, extra-dimensional subtlety to Born in the USA substitutes an objective sympathy for Vietnam-vets with subjective undercurrents of scorn and contempt. Author, Jim Cullen writes of Springsteen’s power to be:

… very much a man of his time. I have been… impressed by the way his life and work resonate with some of the most important themes and figures in American History… [H]is work represents the latest chapter in a story that includes Woody Guthrie, Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan.

(Jim Cullen; p2-3; “Born in the USA: Bruce Springsteen and the American Tradition”; Wesleyon University Press, 1997)

Unlike Dylan’s The Times They Are A Changin’ though, Born in the USA‘s patriotic vibes outweighed anything it had to say at the time. It is still being argued over today: public forums, like YouTube, are inundated with regurgitated arguments advocating patriotism over remonstration, and vice versa. Some instead contend that Born in the USA was a sympathetic portraiture of American Industry; they must have missed the phrases “The first kick I took was on the ground” and “Hiring man says: ‘Son if it were up to me’… He said: “Son, don’t you understand?” In response to pop and politics, author Brian Longhurst suggests that the beginning and subsequent perpetuation of its relationship:

… is often presented as a kind of liberation from the dullness of American and British life of the period. It is seen to have opened up new possibilities of self expression and to break down the conventions of stuffiness of everyday life… there is something inherently oppositional in rock… [characterised] as the music of protest, the ‘movement’ or the underground…

(Brian Longhurst; p106; “Popular Music & Society”; Cambridge; Polity, 2007)

The song’s rallying chorus then beckons listeners to reciprocate, like a nationalised anthem would: “I was… Born in the USA… I was… Born in the USA…” Springsteen sings, as if the only affiliation he, his fans and the protagonist have with the United States of America is the fact that they were born there. Why not: I’m a part of the USA? Too communistic. I am the USA? Too hedonistic. I respect the USA? Too untruthful. So much is trying to be said through such a funneling phrase, its epithets escape. But, anything else would have been familiarly rebellious, along the lines of: Fuck the USA. Censorship would have demanded controversy, and Springsteen would have been lumped into the same vilification as the American Government. We know by now, what he wants to say – nothing should be taken at face value. So how on Earth did anyone – let alone former Republican President Ronald Reagan – misinterpret one of the world’s most televised protest songs?

***

Four years ago, I would have hated this song: publicised Americans fanaticising its chorus like some twisted badge of honour, their country largely responsible for the past three bloody (mainsteam) wars including Vietnam, and an escalating Second Gulf War. Being a leftie, the immediate stench of right-wing politics was a detrimental put-off. Whatever it had to say was swallowed up in its infectious chorus, while Springsteen I personally blacklisted under patriotic sycophant. It wasn’t until the October 2007 release of album Magic when I started backtracking through his success, that I came to understand what Bruce Springsteen was all about. Reorienting its context into the present decade’s music allowed me to overcome my political prejudice. Subsequent acoustic versions of the song – first, during a Reunion Tour from 1999-2000, and second, during his Devils & Dust Tour 2005 – were scathingly clearer, rougher and considerably less anthemic. Reunion Tour was notably bluegrassier, while the Devils & Dust outcry contained only a harmonica and an amplified stomping board. Without Federici’s and Weinberg’s obfuscating piano/synth/percussion, Born in the USA shone through in a typically Bob Dylanesque physique.

The 1984 cut is musically pop of the decade, though – especially with Federici’s synth overture. Something in the style of Eurythmic’s Sweet Dreams (Are Made of This), fused with rock ‘n’ roll to the feel of Van Halen’s Jump or Bon Jovi’s You Give Love A Bad Name. However, Born in the USA‘s catchy, two-bar repetition of notes is characteristically folk in origin – to the effect of Dylan’s The Times They Are A Changin’. Each verse is accompanied with the same notes, making the chorus verbally rather than musically apparent when Springsteen sings those now infamous words. Its first iteration at 0:34 has only a percussion and synth accompaniment. A single, preamble piano-note accompanies each repetition, salvaged from the previous verse and the song’s introduction. Atypically, bass/guitar/(more)-percussion begin after the chorus’ first appearance. At 2:28, it reverts back to its original state at 0:34, giving the fifth verse a sort of rebirth coincidentally with the protagonist’s “[Coming] back home to the refinery.” The song starts over again, despite its miniature reiterations like representational days, months or years. At 2:55, just after “I’m a long gone Daddy in the USA…” the chorus starts-up again like a makeshift eulogy as all the instruments clamour together towards a fade-out end. As if the only worthwhile thing the protagonist has done is being “Born in the USA…” only to beget the next generation; because the song really doesn’t stop, it just simply fades away.

To me, what this song reminds me of, and what my interpretation of it is, are two different things altogether. I can never let go of fully, Born in the USA‘s all-encompassing American-vibe. But I can see through it instead, envisioning it rather like Charles Yale Harrison’s Generals Die in Bed and its nameless, everyman protagonist written in the first-person. What that book had to say, and what this song has to say, are one and the same: all war is bad. And war hasn’t changed. And what frustrates me more, is that somehow we didn’t get it the first time when someone like Harrison – who had endured WWI – published his novel in 1930. Springsteen wrote his song in response to soldier-friends’ accounts from Vietnam, and it echoes many a Vietnam veteran’s struggle for acceptance after its eventual loss.

But personally, I envisage Born in the USA rather like a requiem – a funeral song. The heavy-handed snare-drum exacerbates the nature of the human heartbeat, which is dying. Springsteen’s raspy voice, bestial and animalistic, howls the lyrics in pain, while the synth that is the Political steam-train called America, persists in chugging-on relentlessly. Every repetition, a propagandist reiteration advocating war, promising hope and stifling change. Every heartbeat, an obstacle; towards the end, arrhythmia – finally fading away into obscurity and death. Born in the USA may fuse multiple musical styles into one successful – albeit misinterpreted – form, but it is the misinforming politics surrounding it which interest me more. On a larger scale, Born in the USA is an excellent, demonstrative example of the stupidity of governments, the stupidity of warfare and the underestimated power of patriotically musical indoctrination. Largely though, it is the stupidity of everyday people which amazes me, to hear one thing and think another. Maybe I like this song because it has something to say, rather than for music’s sake, or perhaps because of all its continuing, peripheral controversy. It certainly isn’t something I can listen to over and over again, though – just like politics, really. Nor do I feel like singing it aloud, because of the chorus’ outwardly-appearing patriotism. I am not American; I am proud not to be American. Why should I sing, let alone dance, to a song contrived through so much pain and suffering, exploitation and deceit?